Farcasting

As the seventies went ill for America, so for the Fender Electric Instrument Company. Its new masters at CBS, Inc. got right to work shaving away anything that looked like a superfluous cost, and the results were just the operational excellence you’d expect: shoddy machining, warped cuts of wood, wonky intonation and a neck joint that wouldn’t stay in place because they took it down from four bolts to three. Yet love knows no season, and someone, somehow, managed to lure Seth Lover (first genius of our story) into the midst of this mess to design a Fender version of the humbucker he’d invented for Gibson. He came up with a piece of electronics that growled like a Gibson and chimed like a single-coil at the same time, with a ten-thousand-ohm output to drive any rig to its natural eleven. Jonny Greenwood’s Starcaster has them, Lee Ranaldo soldered them into his Jazzblaster, but they’re above all the mark of the seventies Telecaster, along with that cussed three-bolt joint and the narrow, rounded neck with the truss rod protruding in a bullet shape at top. On the merits these are not the best guitars ever made, but they are absolutely my favorites, a flowering of genius in an age of decline. Two of them live in our house: one a careful recreation, the other vintage and older than I am.

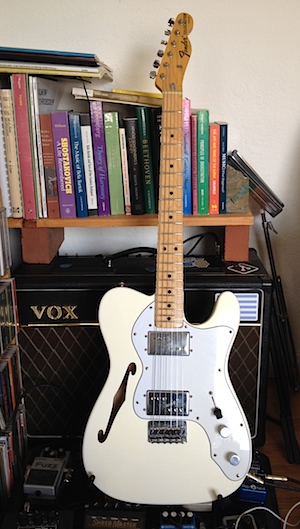

Pindar dates from 1972, the first year of humbucker Teles in various styles, including the Thinline. A couple of years earlier Fender had noticed that their wood stock was starting to get heavy, and Roger Rossmeisl (second genius of our story, luthier trained like his father in Mittenwald) had proposed to them that a solid-body could be made lightweight and beautiful by carving out the left side like a violin. Forty-odd years later, his invention came to us. In the dark decades between someone in Massachusetts had sanded off the finish, dressed the frets down to nearly nothing, warped the pickguard in the sun or next to a radiator, let the case rust in a barn, and as a final insult given it strings one gauge too light. But on playing a first few notes I got such a look on my face, J. tells me, that she consigned me the guitar straightaway, never mind that we’d actually bought it for her. Then I tried to pull a plastic knob off the pickguard and ended up taking the entire instrument apart, in the process assaulting the knob with every tool in the house, including plumbing and gardening tools, and gouging the hell out of my hand. I ended up snapping the knob to bits with tin snips and discovered a) a rusted-on nut that would absolutely not detach and remains under the new pickguard to this day, fused to a bit of the old pickguard; and b) the senseless, skill-less, unmotivated chiseling that the person in Massachusetts had done along the control cavity. We will never know why.

R. was very worried about the irremovable knob and wanted to help pull it off. We consoled her with the news that the stripped body, now picked clean of its parts, would be going to a local “guitar painter.” “Maybe white?” I said to the guitar painter. “What Fender called Olympic white. A little aged?” He got it.

Paisano began life with less distinction, as a right-priced Mexican reissue of the 1972 Tele Custom. This was a hybrid design, putting Seth Lover’s masterpiece in the neck and a standard Tele pickup in the bridge, that slanted single coil in a metal plate that first put the world on notice that Leo Fender was more than an amp tech. That is to say it’s the ideal Telecaster; that is to say it’s the ideal electric guitar. (See Richards, Keith; Yorke, Thom.)

It came in as a successor to my old blue Tele, after I came to acknowledge the hollow left by trading that Tele away. A friendly, elfin hipster brought it over from San Francisco and explained that his new style of music (something with bloops—whatever the kids do) didn’t require “such a complicated guitar.” So began one of the more intense and difficult relationships of my life. It was the feel of its neck in my left hand—perfect line and arc, a handle you’d trust to pull yourself back from a cliff—that seduced me into putting Catullus and a roadrunner on it, and naming it “Paisano,” which a guy sitting on a street corner in Guatemala used to crack himself up by calling me. But having done that, I had to admit that the sound out of the speakers was either too sharp or too dull, never warm enough, however tweaked. I put new pickups in bridge and neck both, rewired it with higher-output potentiometers, installed brass bridge saddles, experimented with a different bridgeplate, all because putting the roadrunner on it had contracted an obligation to make it the guitar it should have been, instead of just trading it away and starting over. In the end I sent the neck out to a luthier in Denton for his secret-sauce refret, and entirely swapped out the body for an American-made ash slab. That did the trick; it came back last week and it sounds perfect. Naturally it’s the ship of Theseus now. Of its original substance, all it has kept is the pickguard, bridgeplate, switches and knobs, along with the all-important wood of the neck; but its form has persisted throughout, guiding the transubstantiation. That is how a guitar becomes what it is.

As to the nature of the perfect sound: there’s a lot of space in it, the space you can hear in any fifties country arrangement with a Telecaster on top. A wide, dry plain with a couple of stretched-out clouds above, and the treble spike shooting up like a jagged rock ridge. The mineral alloys in the pickups—AlNiCo, CuNiFe—give the rocks their colors, just like they streaked the edges of the open-pit mines I used to drive past on my old job, listening to Luther Perkins’s boom-chicka or something British with a lot of echo, whatever it was that day. It’s a prickly fruit with sweet pulp inside. It’s the calling card I’d like to be known by.